We wouldn’t make drugs without chemists. So why make digital health products without behavioral scientists?

Humans are complicated, and changing our behavior is hard. 1, 2 Despite all the hype about artificial intelligence and personalization, most consumer-facing behavior change tools are incredibly unsophisticated, relying on basic self-tracking and superficially-tailored feedback to change behavior. Techniques known to be highly effective, such as such as disrupting habit streaks, and linking contextual cues to behavior, 3, 4 are noticeably absent in most digital health products. Maybe this is why most of these products don’t actually work.

Using science to sell apps—but not to build them

Most consumer-facing apps are not scientifically informed. 5, 6, 7 And even when they are based on evidence, implementation of the science into the product is often poor. 8, 9 This lack of science, however, does not prevent companies from using science to sell apps. On the contrary: A recent review found that over 40% of the most popular mental health apps invoked scientific language to support their effectiveness claims yet just one of these apps linked to published literature. 10

Many of the solutions being pitched or sold to us are behavior change solutions – buy this, wear that, ingest these insights about yourself, and you will be freed from pain, sleep better and lose weight! But peel back the marketing claims, and investors and consumers alike may bristle to find out that—to mention just a couple of examples— sleep-tracking apps can make insomnia worse, 11 and the published benefits of a daily blood pressure monitoring app (whose makers just raised $12 million 12) were based on just 2% of those sampled. 13

An alarming number of companies are publicizing results using inappropriate statistical techniques. For example, conducting what is known as a completers- only analysis involves selectively analyzing only those data from people who completed the trial/experiment, and ignoring the data from people who quit. This approach makes it way more likely you will conclude your product is amazing, because the people who make it to the finish line are inherently more motivated. We want to see your intent-to-treat results, which include the people who dropped out. It is also worth pointing out that the same statistical rules apply to both big and small data. Yet amid the promise of big data, many people have grown increasingly comfortable eschewing the fundamentals. 14, 15, 16 We need to remember that methods matter too: Applying the right statistical analysis can’t overcome bad execution or study design.

The mainstream media, investors, consumers, and industry players have been sold on the idea that behavior change is one appropriately timed nudge away and that we can educate our way toward healthier living. The expectation that exists in the space is wrong: You cannot simply click ‘like’ to change your behavior. 17

So how do you change behavior?

Behavioral science can help us design for behavior change, and build technologies that not only spark change but sustain it. 18

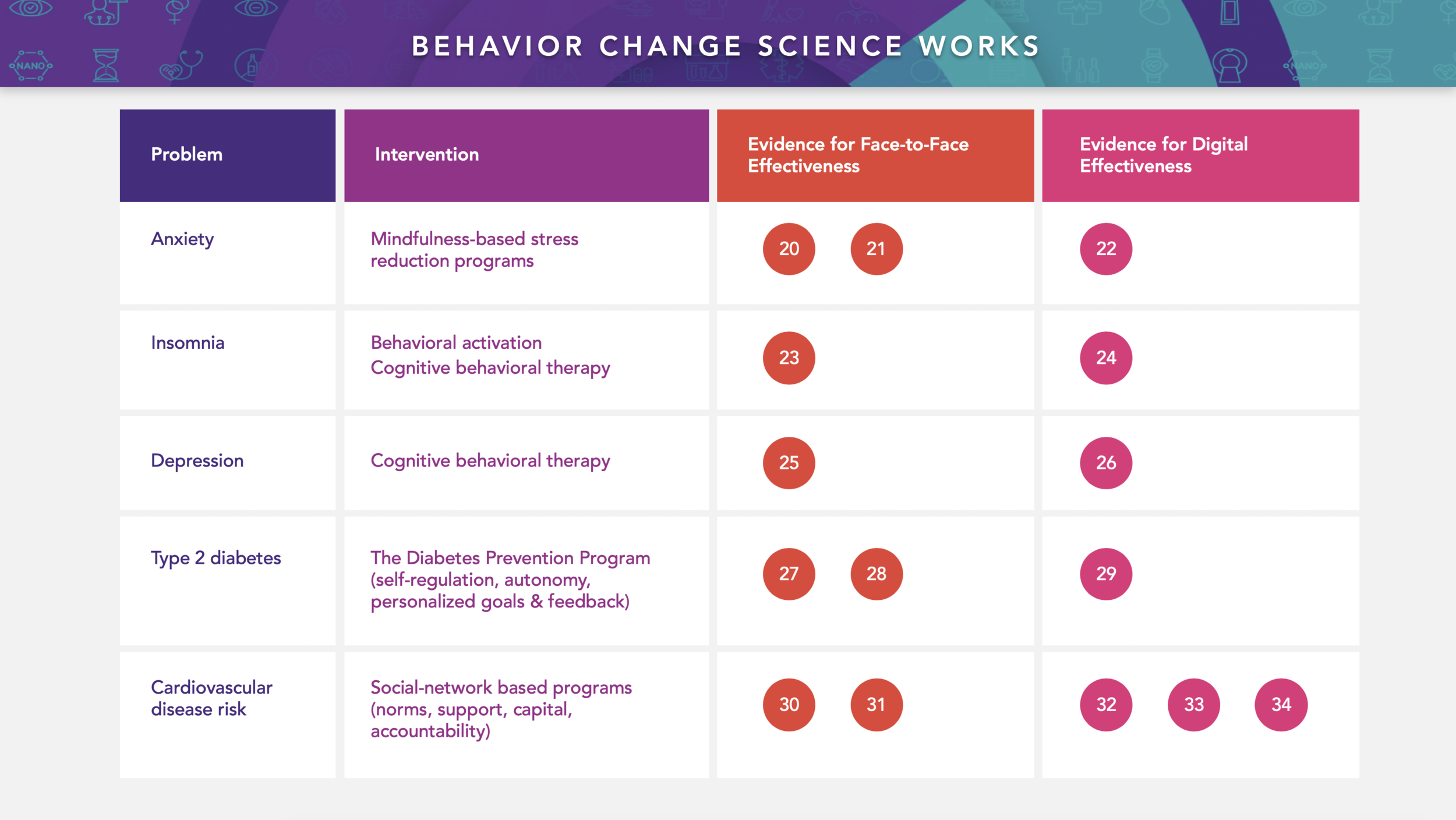

Behavioral science is the empirical study of human behavior across the lifespan. It encompasses fields such as psychology, cognitive science, public health and economics. Behavioral science emphasizes how context, and the social and physical environments, play profound roles in behavior, beliefs, and decision- making. People are different, context matters, and things change. 19 This table lists some behavioral interventions shown to effectively address common health problems.

Links for references below correspond with number bubbles above.

20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34

Behavior change science can tell us what works and what doesn’t. 35 If digital health technology companies ignore behavior change science, they will fail to produce meaningful, long-lasting results. 36

Behavioral science + 21 st century technology

Behavioral science has undergone radical transformation in step with the technological revolution. No longer must we rely on humans to self-report what they are doing—now wearables and sensors can passively detect behavior throughout the day. And in instances where we must ask people questions, new technology-enabled methods can illuminate the behavioral context, such as what the person is doing while sedentary, having cravings, and feeling blue. 37

The data accrued from these newer methods are reinforcing long-held (but previously untestable) hypotheses about the non-linear nature of change. 38, 39 They also enable us to intervene at the right time. 40, 41 In other words, we can get closer to automating human support than ever before. These new data also provide strong evidence that conclusions drawn from group-level data are extremely imprecise for individuals. 42 Fortunately, we can now optimize interventions at the individual level and realize the power of behavioral phenotyping. 43

For example, let’s consider how people react differently to self-tracking. We know that some people reject it because of waning motivation – they get negative feedback and stop tracking themselves. Measuring individuals’ determination, resilience, and/or coping style can provide insight into who will benefit from consistent tracking and feedback. For those who respond poorly to consistent tracking, reframing failure as within one’s control can overcome the tendency to avoid. 44

Wellness apps: A behavior change opportunity

Historically, our focus has been on helping people once they get sick, focusing our investment dollars, product pipelines, and healthcare reimbursement strategies toward treating disease. On its face, this makes sense: There is a lot of sickness to treat. Six in 10 US adults have at least one chronic disease, and four in 10 have two or more. 45 By 2030, the number of adults with three or more is estimated to almost triple from 31 to 83 million. 46 Including lost productivity, the economic burden of chronic disease is estimated to be a staggering 20% of our gross domestic product or $3.7 trillion. 47

But, what if we helped people before they got sick? What if we could recoup some of that $3.7 trillion, and pump it back into our economy? Lifestyle behaviors drive most chronic disease incidence, morbidity, and mortality. 48 These behaviors include smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, insufficient physical activity, and poor sleep habits. 49 With the help of science, these behaviors can be changed. And while there exists a dizzying number of consumer-facing wellness apps that claim to change these behaviors, very few have published evidence to indicate that they do so in any meaningful way. 50

Shockingly, even highly valued healthcare startups do not publish peer-reviewed evidence on their apps’ effectiveness. 51 If we are to move the needle on health, this indifference toward evidence and limited use of science must come to an end. We simply cannot afford to fall victim to the illusory truth effect whereby we accept evidence to be true based on how often we hear it repeated.

Digital health won’t advance without behavioral science

Digital health companies should have behavioral scientists embedded in their product development teams from the very beginning. Companies should also include behavioral science in their medical affairs departments, for both evidence generation and strategic leadership. The most forward-thinking companies will have chief behavioral science officers. 52

Within product development, behavioral design should operate in concert with user- experience design. 53 Behavioral design involves translating science into products and services. In addition, behavioral science should be positioned to work alongside analytics and data science. Establishing behavioral-data science architecture is necessary for many reasons, including planning experiments and interpreting users’ engagement data. Digital health companies need to go beyond a focus on the number of monthly or daily active users and ask themselves, what effective engagement looks like. 54, 55

Four questions for evaluating a product’s behavioral claims

-

What evidence supports these claims?

- How was this evidence generated?

-

How is behavioral science informing product/service design?

- Who is responsible for pilot tests/experiments?

Remember: Behavior change is hard. Science helps.

Dr. Gina Merchant, PhD, MA

MDisrupt Guest Blogger

Dr. Gina Merchant is a behavioral scientist specializing in digital health. She is an expert in user/patient engagement, how our social networks influence our health, and behavior change design. Gina has a PhD in Public Health, and an MA in experimental psychology.

Disrupt has a network of behavioral scientists; If your company needs this type of expertise to help you build your health product, talk to us—we can help.

More details on the

More details on the