Written by Ruby Gadelrab, CEO and Co-founder of MDisrupt

Most of us in the health industry want to get meaningful health products to market, and to the people who need them, as fast as possible. Yet in the growing healthtech sector, despite over $50B invested since 2011, there have been relatively few successful exits.

Over the past five years, since before we founded MDisrupt, we have worked with, advised, reviewed or consulted for over 100 healthtech companies. We were surprised to find that the mistakes these companies are making are shockingly consistent. Even more striking is that many of these mistakes are completely avoidable. Here are a selection of the most common things we have seen.

Many of the health products we reviewed often just don’t solve a real problem in healthcare. At best, some are nice to have, but for the most part many of the companies we talked to hadn’t actually understood the workflows and nuances of what their intended customers were trying to accomplish. Often it’s a case of trying to commercialize a technology by “backing into” a perceived problem.

In many cases entrepreneurs start with a technology and then seek a market. In one case, an entrepreneur had built software for physicians of a particular type of medical specialty, but had never actually spoken to one of those physicians. She hadn’t engaged them at any point before building the product to check that it solved a real problem, or during the build to understand what features were important.

Understanding your target audience—and especially where the user fits within the complex healthcare setting—is critically important when building health products. There are many nuances, stakeholders, workflows and dependencies that differ for each case and are critical to understand. Involving healthcare experts from your target audience early and throughout product development is mission critical to building a clinically viable health product.

In short, no product-market fit = little or no scale.

Having product-market fit is one key to building a clinically viable health product. Equally important is commercial viability, in particular, ensuring that your product creates value for its user. Does it come at a price point where the ROI of adopting it is clear? How much does it save compared to other technologies or to the status quo? How much does it cost to implement? Do the combined costs of the product and the implementation provide a compelling financial argument?

To answer these questions (which stakeholders WILL ask) it’s essential to do a Health Economic Study or Health Economics Outcomes Research (HEOR). This needs to be conducted by an experienced health economist and definitely not by the internal commercial teams.

One type of Health Economic study is a Cost Effectiveness Analysis (CEA). The CDC has a great definition and example here.

“Cost-effectiveness analysis is a way to examine both the costs and health outcomes of one or more interventions. It compares an intervention to another intervention (or the status quo) by estimating how much it costs to gain a unit of a health outcome, like a life year gained or a death prevented.”

There are several different types of health economic models. Different stakeholders prefer one over the other and they are not easily converted. For example, self-insured employers may prefer a Budget Impact Analysis. For either channel, you will absolutely be required to show these analyses as part of a BD negotiation before they would even consider a pilot.

Beyond the healthcare setting, another mistake entrepreneurs often make is overestimating what consumers are willing to pay for a health product. While it’s good practice to conduct price elasticity studies to gauge the value consumers perceive in your product and where the right price point may be, it’s important not to over-index on these results. Consumers behave very differently in research settings than in a real world setting when they have to pay for health products.

Even if you have the BEST technology that solves a REAL problem, if the economics don’t work, then there is no viable business.

Many healthtech companies we spoke to, had no healthcare experts on their leadership teams at all. Very few had hired medical professionals as employees, consultants or advisors, and those that had them rarely involved or listened to them. This feels counterintuitive if you are building a health product. As a marketer, I (Ruby) have been hired by multiple companies to consult because the founders know and freely admit that they don’t know marketing and so they hire an expert. However, rarely have we seen them say the same thing about hiring medical people.

In one case, I met a founder who was building a clinical genetic test and seeking advice on his first hires and advisors. When I suggested that the first hire should be a medical geneticist, or a chief medical officer, he was horrified and asked “Why would I hire that skill set now – what would they do? What value would they bring?” These questions are answered by Dr. Daniela Crandall in her blog The Critical Role of Medical Affairs in a Healthtech Start-Up.

After we founded MDisrupt, we were overwhelmed with support from the healthcare industry. Hundreds of people reached out to say how glad they were that we founded the company and how much Medical Diligence is needed. As we started talking to them, they all told us similar versions of the same stories of their experiences in healthtech companies:

Many were hired by healthtech companies for “optics” purposes only

Very few had a significant role or say in product development

When they suggested that certain mission-critical studies should be done they were often ignored or put on performance improvement plans for overstepping

Numerous medical professionals told us they were asked to join sales calls and state their name and credentials only and not speak beyond that

When marketing material was created, it was rarely passed to the medical teams to review for accuracy of clinical claims. On the rare occasions that it was, commercial interests often trumped medical truth.

Most of the healthcare experts we met were talented, passionate and eager to be part of the creative disruption of health care. Although they had had bad experiences, they still had faith that if healthcare professionals could be given a real seat at the table and a significant voice in building health products, they could help accelerate the path to market in a responsible way.

There is no doubt that health care needs to be disrupted and to become a better experience for all of us. Healthcare experts and healthtech founders are equally frustrated and united in the mission to make this happen quickly, but it needs to be done responsibly. Healthtech entrepreneurs can save themselves years of time and millions of dollars if they engage health experts early and often in a meaningful way.

Many of the founders we talked to mistook “scientific” advisors for medical ones. Often when we asked where they were seeking medical guidance, we heard “Prof. X from high profile institution Y is one of our founders/advisors/board members.” We would say, “That’s great, but does Professor X have any medical training? Has he or she ever commercialized a health product?” Usually the answer was no.

It appears that many healthtech entrepreneurs don’t know the difference between scientific and medical expertise. It’s important to have the right type of expertise for the task. Jill broke this down in her blog where she defined the differences between scientific and medical expertise.

Even scientific discoveries which are peer reviewed in high profile journals and widely cited need to be successfully translated into products that can be used on patients. Great science doesn’t always translate into great health products‚ the discovery may fail on some other aspect of its clinical or commercial viability (see the point about product economics above, for example). There is a difference between scientific validation and clinical validation. Most scientific publications are not designed to demonstrate the clinical validity of a medical test or health-related claim. (We will address this in a future blog.)

Sometimes healthtech founders are not even aware that there is a scientific or medical discipline well-matched to the task they are trying to accomplish. An example of this is where a health product is designed to incentivize behavior change. I have met numerous founders who gave the role of creating these products to their Head of Product, typically a person with a commercial background. It comes as big news to them that behavioral science is an actual scientific discipline and there are specific scientifically proven methodologies for incentivizing behavior change. In her blog, Dr. Gina Merchant, who has a PhD in behavioral science, describes why engaging a behavioral scientist is so important when building health products.

When building a health product, the bar for evidence that it ACTUALLY WORKS and is SAFE to use on real humans is much higher than when building consumer products.

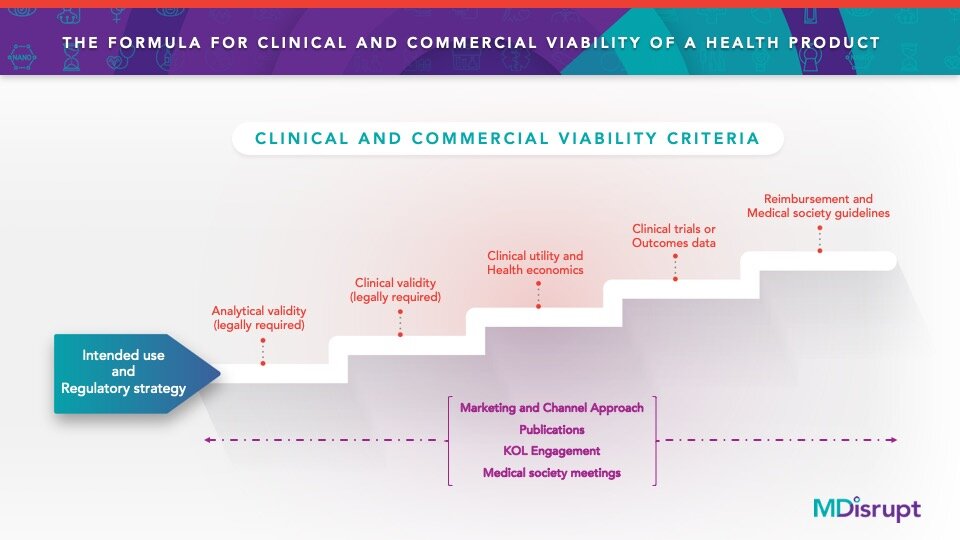

The studies aren’t a “nice to have”—they are mission critical for building clinically and commercially viable health products. The studies that need to be conducted are an essential part of the formula for successfully building a health product. This formula isn’t magic or a secret sauce: It is well known by healthcare professionals and is a standard series of studies and activities that every company building a health product has to do.

We outlined these essential steps here in our blog The Formula For Widespread Adoption of Health Products that Every Healthtech Investor and Entrepreneur Needs to Know. As we talked to healthtech companies over the past few months, we realized that this formula seemed to be unknown to them. Many hadn’t planned on doing these studies simply because they didn’t know they had to.

The first step in health product development is to define the intended use statement (also called the intent of use). This statement informs the regulatory risk category and determines the types of studies that will be needed. Failure to optimize the test for its intended use will result in an unacceptable number of false results. But done properly, the intended use statement will serve as the “North Star” for product development, medical and scientific affairs, marketing, and financial forecasting.

Many variables can influence the performance of a test, such as population characteristics, the prevalence of the target condition of interest, the setting, and the type of test, among others. Thus, it is important to design the performance evaluation studies to match the intent of use.

The intended use of a test describes:

The clinical purpose of the test: e.g. screening, diagnosis, prognosis, risk prediction, therapy or treatment selection for patients

The type of technology used: e.g. next generation sequencing, spectrophotometry, or electrophoresis

The target condition e.g. disease, disease stage, or any other condition of interest

The analyte being measured e.g. DNA, HbA1c, LDL, Vitamin D

The type of specimens acceptable for testing e.g. whole blood, plasma, serum, tissue

The location where the test is conducted e.g. clinical laboratory, point of care, home use

The type of results: e.g. quantitative, continuous, ordinal, or qualitative

The population for which the test is intended e.g. adults over age 50, adults with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder who have had an inadequate response to at least one psychotropic drug, high risk pregnant women

Skill level needed for interpretation of the test the need for a trained or skilled user of the test or test interpreter

In our experience, founders often don’t understand the concept of intended use. When we ask them who the product is created for, they often answers “Everybody,” or a very wide subset of the population. Usually the reason founders are keen to maintain a broad intended use is for commercial purposes; they don’t want to limit their TAM and SAM projections, particularly when fundraising. However, the fastest path to market is usually the simplest, narrowest intended use. The intended use can be expanded over time as additional studies are completed to substantiate the claims.

I (Ruby) have consulted for about 35 companies over the past two years. Almost all of them ask me one or more of the following questions:

How do I get a deal with a self-insured employer (SIE)?

How do I get physicians to buy and use my product?

How do I get a deal with a health system?

How do I acquire consumers?

I will save consumer acquisition and health systems for future blogs, since they are entirely unique channels. Here’s what’s important to know about self-insured employers and physicians.

Self-insured employers

Often entrepreneurs choose to access this channel as they believe it’s a way to accelerate commercialization and revenue before the necessary studies are done to get into medical society guidelines and reimbursement. This assumption is often not the case, SIEs also have a minimum bar of clinical evidence required. SIEs may consider small pilots that are usually funded by the healthtech company without seeing the studies. But ultimately, the final decision for adopting a health product widely in this channel will be made by a CMO (Chief Medical Officer). She will often ask for the same level of clinical evidence as required in a healthcare setting.

In addition, the ROI analysis is also critical for this channel (see product economics section above). Again, if the economics don’t work, there is no opportunity for scale. Our physician consultant and expert Dr. Ron Leopold covers this in his blog How Healthtech Companies Can Successfully Access the Self-insured Employer Market.

Physician adoption

When it comes to achieving widespread adoption in a healthcare setting by physicians, there are two additional critical steps (assuming all the other steps have been done correctly). These are

Incorporation into medical society guidelines

Reimbursement

Healthcare professionals and scientists are the most skeptical audiences. Glossy marketing material alone isn’t going to convince them of much; in fact it will barely get their attention.

The biggest influencers of these professionals are their peers. For them, convincing content needs to be in the form of credible data and evidence. And the most effective communication medium is medical society meetings.

For healthtech companies, a critically important part of entering this channel involves developing a KOL (Key Opinion Leader) program. KOLs will help to generate the data and evidence necessary to get into medical society guidelines, convince payers to reimburse for their products and will also create “medical influencers” who can educate their peers. How a KOL program works and its purpose will be addressed in a future blog.

We have often heard from healthtech companies, “We don’t have time to do all these steps; these studies take years; we need to get there faster – what can we skip?” The reality is that when it comes to health products, there are no shortcuts.

So how does a healthtech company in a rush to commercialize get there? Well, the easiest way is to engage healthcare experts early, listen to them and follow the formula to avoid making costly missteps. The hard way is to try to skip a few steps and waste years of time and millions of dollars trying to recover.

The path to getting your health product widely adopted may be longer than for a consumer product, but it doesn’t have to be hard. At MDisrupt, our goal is to help healthtech companies create clinically and commercially viable health products. We have built up a network of experts from across the healthcare continuum and they are all passionate and eager to help healthtech founders get the most impactful products to patients faster. If you need a healthcare expert, talk to us.